The Rugbys “You, I” (Amazon, 1969)

Mike Shanley

Back when 5 & 10 (or “Five and Dime”) stores were easy to find in Downtown Pittsburgh, during the early ’70s, there were more things than the smell of roasted nuts that could win over a kid’s attention while moms looked at discount clothing or other boring things. There were crates of records – albums and singles. Sometimes the 45s came sealed in plastic with three records available for one price. They also came packed in white boxes, lending a bit of intrigue to them.

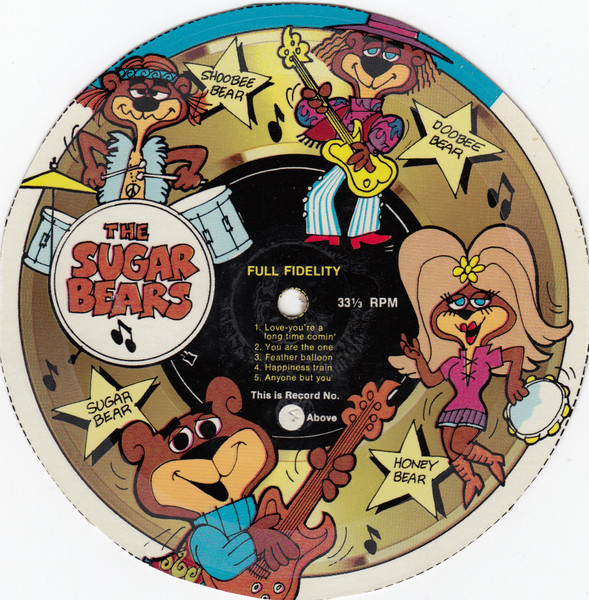

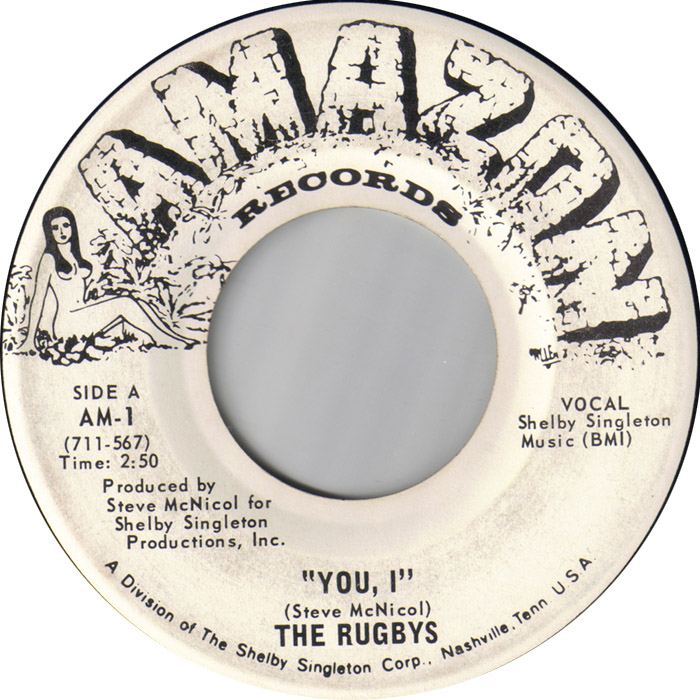

These singles weren’t leftover copies of “Close to You” or “Billy Don’t Be a Hero” or other Top 40 fare. These were acts that never quite made the big time. The ones that fell into my hands were on labels like Decca and UNI or smaller imprints like SSS International, Plantation or Amazon. Incidentally the first set of initials were not related to either Germans during World War II or a Pittsburgh industrial label (that wouldn’t happen for about 15 more years), nor did the third name have any connection with a current corporate monolith. The three S’s stood for “Shelby S. Singleton,” a Nashville record producer who had a hand in all these labels.

For a young kid who loved devouring records in general, it didn’t exactly matter if the music wasn’t that great. They were something new to check out. But when a record was great, there was a good chance that it would land in heavy rotation on the phonograph and stay there.

The Rugbys, from Louisville, Kentucky, produced one such single. It came on the Amazon imprint, whose art featured the label named written in big letters above the spindle hole. On the left side of the label was a drawing of a young lady with long flowing hair covering the important body parts. As a youngster, I overlooked the drawing, being more interested in what I would hear when the needle on my Mickey Mouse record player dropped into the groove.

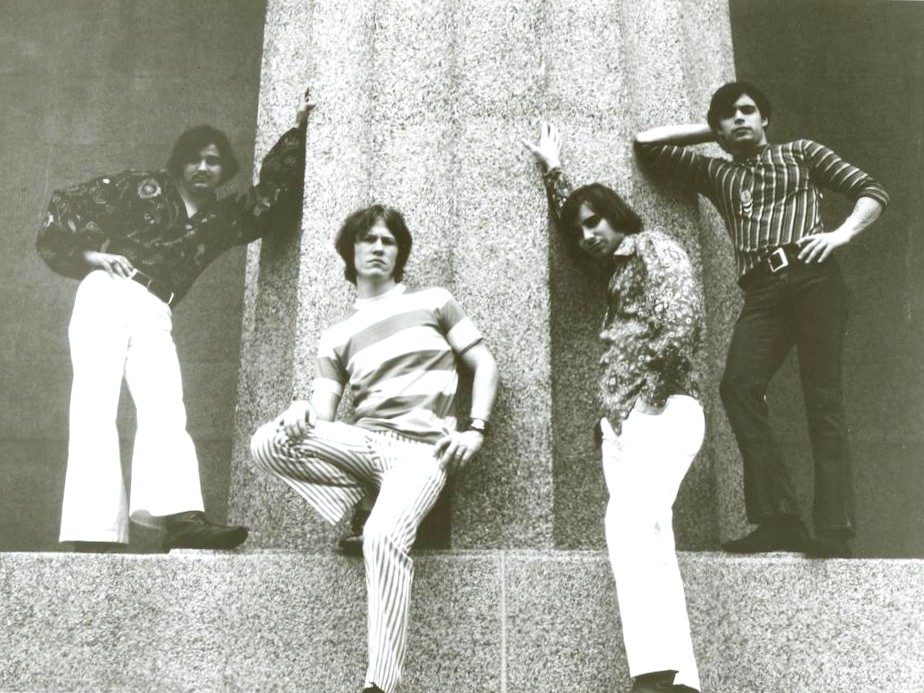

The sound that launches “You, I” resembles an angry bumblebee, buzzing close to the microphone. As a kid, I knew it was a guitar but I liked that it didn’t sound like one, at least not yet. After a few seconds the source of the buzz, guitarist Steve McNicol, goes into a chunky riff and the rest of the Rugbys kicks in.

McNicol, organist Ed Vernon, and bassist Mike Hoerni (yeah, sure that was his real name) play staccato stop-start chords during the verses, while drummer Glenn Howerton keeps going. Sounding like a distant cousin of the Kinks’ “Till The End of the Day,” the riff’s arrangement adds tension, which the song needs since the lyrics were on par with songs I was writing back in my grade school days:

You … [stretched into two syllables]

You don’t want me to

Fall in love with you

What else can I doooooooooo

I, when I think of you

Every time I do

All I see is bluuuuuuuuuuue

[I skipped ahead to the second verse, just for the record.]

Clunky lyrics aside, they’re creating suspense as they keep starting to rock out after every third line, only to cut back to staccato during the vocals. It eventually leads up to a wah-wah guitar solo that sounds both vocal and a little whiney. McNicol must have been listening to his Hendrix and early Deep Purple records and was ready to use that pedal his own way. Combined with the band’s falsetto vocals behind the solo, he’s not been fully successful. In fact, the end of the solo almost sounds like a mistake. But the best was yet to come.

After another verse, where McNicol goes from pleading back to a garage rock snarl, the song starts to slow down. As it does, the guitarist unleashes a blast of wah wah that sounds like a feral cat ready for a brawl. As McNicol and Vernon hold down their final chord, Howerton’s drums cue the ending. It felt like the whole song was building up to that moment, a big ugly noise that would make any hip eight-year old record fan laugh every time.

A few months after buying the “You, I” single — or looking back, maybe it was just a weeks later — my mom returned to the 5 & 10 and came across Hot Cargo, the Rugbys lone full-length album. Spread over an entire album, the quartet had a bit of a Doors vibe going, at least when McNicol handled the singing. Vernon’s songs were equally catchy, though it was hard to take his gothic “Wendegahl the Warlock” seriously after hearing him mock (presumably) southern preachers in “Song To Fellow Man.”

That initial copy of the “You, I” single got lost somewhere along the way, but I came across another at an estate sale, with the same white label, as opposed to the color labels that other pressings and the album featured. The song holds up, though I think I was more excited to hear the B-side, “Stay With Me,” remembering that, in a flip of the typical standard, the album version faded out before the band went into a brief freak out in the coda. Hot Cargo, on the other hand, is still on my shelf though I picked up another copy (still sealed!) just a few years ago since my first copy amassed a few deep scratches over the years.